Medea by Eilish Quin

Necromancy is not the solution. Necromancy is the question, and the answer is yes.

Finally, a retelling of the Medea myth. And such a good one at that. Clear-cut 5 stars.

Personally, I have always found this myth fascinating ever since I read the play by Euripides as an undergraduate all those years ago. I also remember being shown a clip of a Kabuki version of the play in class. It’s been stuck in my head since. Now that I’m a mother of a young child myself, I can’t help but think about this story and what it means for a mother to kill her own children just to spite her faithless husband. Could any mother actually do that? There’s a recent case in Singapore of a father who tortured his own child for years before eventually killing her. It’s not the only case. It seems like every few months, something like this ends up in the news. It’s still horrific, don’t get me wrong, but no longer surprising. I don’t think any of us are truly surprised anymore when we read about violent men. Similarly, gods killing/eating their own offspring is nothing new. No one expects fathers to unconditionally love their children. But when it’s a woman who commits such an act, it feels genuinely transgressive. I can’t rationalise that feeling away no matter how hard I try. I wonder why.

I want to talk about the author’s note. To my surprise, it was an essay analysing the myth and its evolving representations across history.

“Any modern portrayal of Medea presents an interesting challenge. She commands a thousand associations and identities within the strange terrain of her semidivine body—she is at once the archetypal femme fatale, a mother, a sorcerer, a sister, a murderess, a daughter, a kin-slayer, a wife . . . She is saviour and Siren contained in a single, bewitching person . . . She has emerged as a condensed symbol of nefarious womanhood and a perpetual outsider, mediating a strange dichotomy between her native wildness and the chaos of the natural world and the carefully constrained and familiar realm of the domestic . . .

For Euripides, the native savagery of Medea, who is so volatile and brutal in her intensity, stands in flagrant opposition to the order and civility of the Greek city-state. Her mere presence in Corinth is a destabilising force. Perhaps, femininity, together with foreignness, functioned in Ancient Greece as they do in the contemporary period, under fairly consistent policing, encompassing a kind of embodied, unspoken relational threat to innumerable societal structures that any hierarchical society might depend on . . .

Ineffective wives breed ineffective mothers, posing an almost unmentionable peril to the nuclear family model . . . Medea’s story is in part so captivating because it represents a kind of horror almost too arduous to hold with any coherence: the murder of children . . .

I have crafted [this story] not to copy or detract from its original retellings, but rather to explode it. In this novel, I propose that Medea is not simply misunderstood—for that would be overly simplistic—but that she is, in all her complexity, a product of the impossibility from which she emerges. My [novel] is superficially interested in feminist reimaginings of a classical text, but more than that it is concerned with monstrosity in an age and setting where monsters existed everywhere . . . In a sense, the writing of Medea was my own clumsy attempt at necromancy—the resurrection of an ancient story . . .

[S]orcery is a family affair, and as such, it parallels a certain degree of intoxicating beauty, attachment, and dysfunction . . . There is a peculiar intersection between trauma and magic, transcendence, and psychosis that even the most diligent student of psychology or earnest disciple of spirituality might find difficult to parse . . . there is some pressure in the modern world, perhaps unconsciously, to label magic as real or unreal—a tension between belief and scepticism.”

The long quotes above are my favourite parts of the author’s note. It really is my favourite part of the whole book. I wish I could give it six stars out of five.

In this retelling, Quin attempts to reconcile Medea the sister/mother with Medea the witch. We already know she is very powerful and capable, so why would she throw it all away for some guy? Fratricide is a serious crime. Unless…? If she really was that good a witch, perhaps death itself was no barrier to her. Perhaps she believed that she had no other choice. Perhaps this love she felt for the rando who popped up on her homeland was engineered by a higher power. Quin takes all these ‘perhaps's and spins them into a highly original and compelling narrative.

By introducing necromancy into the original myth, I do think that Quin did a masterful and convincing job of creating a rationale behind Medea’s actions. To get her brother, Phaeton, out of her father’s clutches, Medea has to convince Aeetes that his heir was truly dead. She chops Phaeton up before sailing away, but reassembles him immediately after and brings him back to life. She was the original Doctor Frankenstein. However, she can’t brag about it or let anyone besides Jason know because Aeetes would hunt them down. Not to mention, necromancy is heavily frowned upon and considered an affront to the gods themselves. The price of freedom is her reputation, and her brute of a husband has no qualms blackmailing her to keep her in line. Later on, to free her children away from Jason, she takes the same risk but tragically fails, resulting in the extremely steep cost of their permanent death.

Throughout the novel, Medea clearly feels repulsed by Jason and mistrustful of whatever he says. She is, basically, too preoccupied by her own problems to notice much of him or fall in love. He pursues her but she remains cold. Even when they enter into a relationship, he finds her inaccessible. Medea’s aloofness draws Jason to her as he sees her as a challenge and conquest. Athena notes that her “stubbornness will be good for him” as “A hero occasionally needs humbling.”

Medea’s encounters with men have all been bad or traumatic to some degree. Even when she meets the one suitor who genuinely likes her, she is unable to snap herself out of survival mode and appreciate the opportunity, being too afraid of marriage and entrapment. One of the events in her childhood that shaped her fear of men is being inappropriately touched by her sister’s fiance, in a chapter aptly named, “On Mutilation.”

“Over and over again, I found myself pulled against my will back to that afternoon in his chamber, when I was sure my father had set me up to be ruined, when I had realised I was a pawn to the men who populated my life—another frantic animal to be exacted of its usefulness . . . I spent more afternoons than I care to admit crying softly in the dank darkness of the cellar, a wreck of what I once was. It was foolish, I reasoned. After all, Phrixus had hardly touched me. And yet I felt entirely violated.”

In that moment, Medea was just a child torn between her father’s orders and her natural aversion to men. Even though she felt some attraction to Phrixus as he was kind to her, she was right in her suspicion that his niceness was merely a facade. This is a pattern that repeats itself later on in her interactions with Jason—he praises her and affirms her sacrifices, but is quick to turn on her and reject her for the things that she did for him. Medea finds herself in positions where she needs men and craves their approval and acceptance, but is fully cognisant of how little her person matters to them.

“Phrixus would have no reason to suspect deception from me, the child who watched his every move like some sort of pathetic dog eager for some compliment from its master. How humiliating it was to be a woman.”

Part of why Medea cannot be easily villainised is because she has no real avenues for escape. As a woman and princess, she is not allowed to exist apart of men no matter how much she wants to. If she remains with her father, he will marry her off to some guy who will force himself on her to produce heirs like he did with her mother. Her father planned to go so far as to remove her memories and chemically lobotomise her so that she will not be a threat to his rule and would be more compliant, i.e., easier to rape.

“Even if you are frail and weak by virtue of your sex, and your expertise is premature and unpolished compared to mine, you know certain things that we cannot allow you to take out of Kolchis. For this reason, I will be stripping you of your memories, all those troublesome little spars of knowledge that plague your infantile brain, on your wedding night. Once your husband has bedded you, and there is no going back on your betrothal, you will drink an elixir that I brew for you, and it will render you as fresh and new as a little girl.”

If she has to depend on some guy to survive, she’d rather choose the guy. Tragically, it seems like even that illusion of choice was not given to her as she is informed by several goddesses that her ruination was ordained by fate. Having thrown in her lot with Jason, she must find some way to make him successful and secure her children’s future. Earlier, she warns her sister that “It’s madness to tie so much to a man,” but when she grows up, she becomes similarly shackled.

It came as no surprise to me, then, that Medea was queer-coded. Aside from her clear mummy issues, her reaction to meeting Aphrodite in person says a lot:

“I could not summon the faculties to respond, so intent was I upon internalising her face. Her skin was soft and flushed, and her eyes seemed to be a thousand colours at once. Her hair, which flickered madly in moonlit cascades, drifted down about her shoulders, ending at her ankles. Her lips were full and dark, her nose delicate. It occurred to me vaguely that this kind of beauty could be fatal, that perhaps it had already killed me . . . A shiver erupted along my spine, and as her eyes met mine I felt as though a knife had slid into my chest to the very hilt. I must have looked incredibly foolish, slumped over before her, eyes dreamy and yearning. Unbidden, images flashed before my eyes, as I imagined what it would be like to hold her, to kiss the soft skin where her long neck met her collarbones . . . A mirage of faces assailed me then, and I recalled the strange fervour in my breast that could only be inspired by some of the comelier serving girls back in the palace.”

Nowhere else in the text does Medea have such a strong romantic/erotic reaction to someone else. Aphrodite pricks her with an arrow to make sure that she will fall in love with Jason, but the result was dampened or muted in some way. Medea had never fallen head over heels for Jason, or any man for that matter. But the pretty girls who worked in the palace? Definitely. Not that she acted on it, treating it as further proof that she’s not normal. She felt herself bound to Jason out of necessity and some unidentifiable emotion, probably from the love arrow’s poison, but she never loved him. Even the consummation of their marriage could be read as non-consensual on her part.

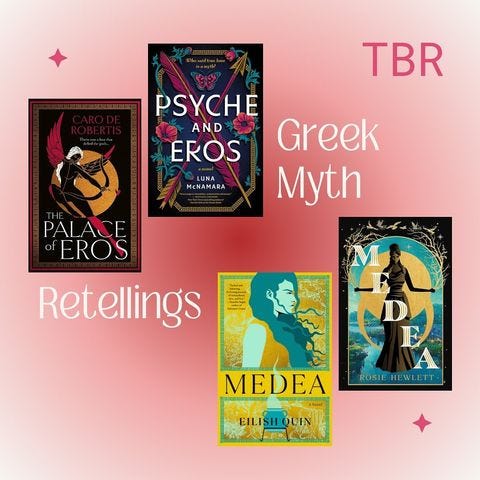

I’m 3/4 of the way through my recent TBR, which I decided on when I realised that I had similar retellings on hand.

I was pretty disappointed by Psyche and Eros after reading The Palace of Eros because of the complete difference in quality and tone. The last book in my compare and contrast exercise is another retelling of the Medea myth and I know nothing of it (it’s brand new) so my expectations are going to be low. I hope I will enjoy it.