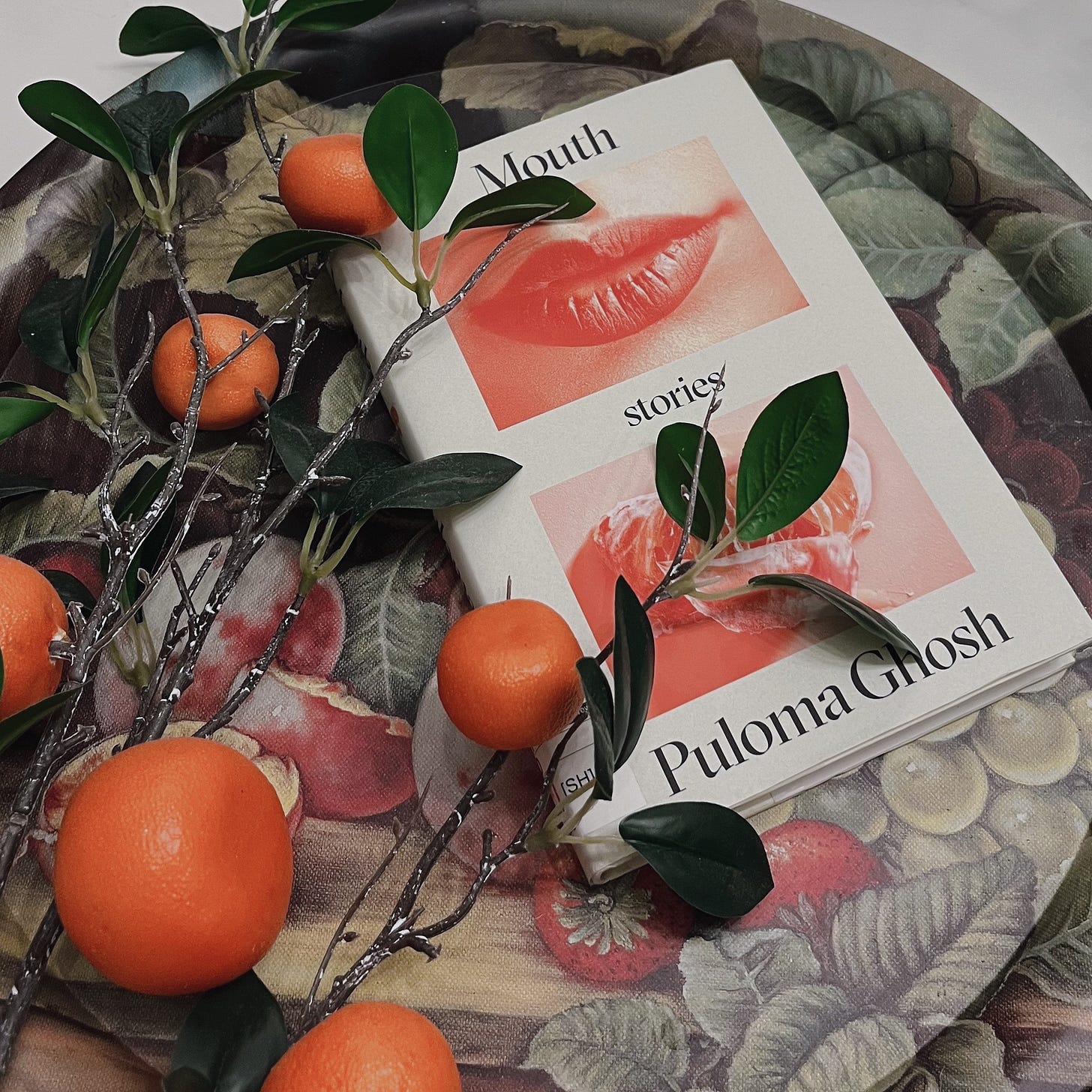

I know it’s only September but I think I’ve found my favourite book of the year. It’s going to be hard to top.

To my own surprise, it’s a collection of short stories. I like short stories well enough but I wouldn’t say that I am partial to them; I tend to like fully fleshed out narratives with progression, but I guess what I’m realising is that a narrative can be fleshed out and have progression and also be economical. It takes skill. Ghosh writes with such acuity and there’s nothing spare or excess about her lines. I went into every story thinking, “wow I really like this story I should say something about it in my book review,” then I read the next story and I think the exact same thing, so on and so forth. I ended up having something to say for almost every story, something I liked or something that scratched that part of my brain that responds to beautiful writing or the idea of dark/feral/unhinged women or gothic tropes. Everything I want to say is definitely not going to fit into one Instagram caption, so here I am.

(1) ‘Desiccation’

This was such a strong story to start off with. Teenaged Meghna comes from a small town where all the boys and men are gone because they’re taken away by some governmental entity the moment they turn seventeen. Her mother works for the Bureau that enforces this rule, making them quite unpopular in town. The official reason is that there is some kind of mega but secret war going on so all the men must be conscripted.

“There were no battles we could see, no bloodshed on soil. Nobody could be trusted to know what was going on because we were surrounded by leaky technology that could see, hear, touch, read. Shortly after, they switched all communications to local: mobile devices bricked, internet access restricted to nearby servers, all packages and shipments thoroughly regulated, landlines hitting an apologetic operator when people tried to dial outside of their area codes."

The overall effect is reminiscient of Orwell’s ‘1984.’ People are kept in the dark and treated as mere pawns (or perhaps resources) for a larger, potentially nefarious, purpose. With communications so severely limited, there’s no way to confirm the truth with other towns or other countries. Entire populations are isolated, vulnerable, and dwindling without men around. People didn’t want to have children anymore because sperm became expensive and they feared having sons just to have their boys taken away later.

In the meantime, Meghna suspects that her ice-skating competitor, Pritha, is some kind of vampire.

“I had seen corpses, which is why I knew Pritha was not alive . . . In a locker room full of teenage girls, she was a plastic ball hidden poorly in a bowl of ripe plums . . . She was just teeth and flesh and empty eyes, no different from a body on a slab . . . Her skin wouldn’t break, and there was no blood; my teeth left white imprints like I was biting into chewed gum”

When the town encounters a rat problem, she catches Pritha taking care of it by eating the rats. Pritha also shares that she got bitten by a tiger long ago, before tigers went extinct. When Pritha talks about where she came from, she says she hasn’t been back “in a long time,” and that shops looked and smelled very different, unlike the “crisp nothing of packaged food” of now. There were real markets with fresh produce and raw meat. It sounds like Pritha’s a lot older than she looks.

This is not to say that Meghna is afraid of Pritha; on the contrary, she desires her, which is in line with her love of other “cold things” like popsicles, pool water, ice, oh, and dead people. Dead people turn her on because imagining herself dead gets her off. She’s wired that way. Sex and death coexist comfortably in her teenage brain. Meghna also desires Pritha because she “wasn’t human but something born in a version of the world [she]’d never witnessed.” As the only other Desi girl in town, it could be that Pritha also represented Meghna’s lost heritage and connection to her motherland. But wanting to go back to the past is akin to desiring a cadaver—there is no future and it’s not healthy. Pritha can take from Meghna but Meghna can’t even leave a single scratch on her. Pritha’s impenetrability (well, save for one location I guess) is a puzzle to me. When I try to think about why the past takes the form of a sapphic teenage vampire, my head hurts a little. Maybe you can figure it out.

(2) ‘The Fig Tree’

“She doesn’t feel like she fits in here any more than she felt she fit in with her white classmates in the earlier years of her school life, before she smoothed out all her foreignness.”

This is the ‘mother story.’ If you’ve read enough, especially enough diaspora literature, for sure you know what I’m talking about. I like this topic, and what I like even better are ghost stories.

Ankita returns to Kolkata with her mother’s ashes, deliberately leaving behind her foreign husband who would taint her homecoming experience. Kolkata is where she grew up, but like her mother, the Kolkata of her past is irretrievably gone. She can’t drink the tap water, she can’t tolerate the pollution. Everywhere, she sees traces of her mother, first in a random woman’s neck, then in the helper’s back, then a stranger standing by the window, then in a woman next door eating a chocolate bar. She is definitely getting haunted, but it isn’t really her mother, more of something associated with her mother. She keeps getting nightmares about her grandmother’s house where she grew up in, and which for some reason, everyone is telling her not to visit, citing it has ghosts.

Just as she is yearning for her deceased mother, she starts seeing impossible things, namely, a woman’s arm wearing her mother’s gold bangle stretching like putty across entire crowds, unseen by others, with the flexibility of Elastigirl from The Incredibles, stroking her face and offering her candy from her childhood. This is quite freaky but such an intriguing image. Whatever it is, whether it’s her mother or mother-adjacent, it is clearly trying to beckon her somewhere, coaxing her with sweets the way a mother would her child, but the disembodied nature of this supernatural arm also suggests that Ankita is dealing with something non-human and not her real mother, whose corporeal form she has just put to rest.

For the first time, Ankita learns about her mother’s past. Her mother was unhappy as a new bride to a man her parents hastily chose for her to remove her from someone unsuitable. She didn’t talk much at first, insisted on working while pregnant, and spent a lot of time sitting under a “shriveled laurel fig” that was believed to contain “some evil spirit.” Ankita saw faces in that tree as a child. (Side note: This isn’t new to Southeast Asians, who believe that hantus live in trees and pontis live specifically in banana trees.)

When she finally gets to the fig tree, she finds a woman in a red sari sitting in it. It can take the form of her mother but it’s also not her mother, likely to be the spirit that’s always haunted the courtyard. It gives her a bangle, a symbol of married womanhood, an heirloom to be passed down from mother to daughter, and says that the bangle is made of her mother’s bones, to help her not miss her mother anymore. It’s a parting gift. Ankita will not return to Kolkata and the house will be torn down, taking with it this mother-spirit that’s tied to her ancestral land.

(3) ‘Leaving Things’

Very interesting story because of the use of the werewolf concept. The narrator is living in a town where people are slowly evacuating because it’s being overrun by wolves. Her boyfriend recently left her. She was raised by a single mother whose husband also left her. She just stays in the apartment, bedrotting and not doing much.

“I’ve always known men to be leaving things. Like my father, who left when I was too young to remember why, and my brother, who left for the army and never came home . . . My last days with Austin confirmed the suspicion I always held: I was born only to become my mother’s silhouette against the oval window of our front door, watching another man walk away. That we would always be a little pathetic, exhausted yet unwilling to part with our empty rooms.”

Early into the story, it is strongly hinted that the wolves that started appearing out of nowhere were actually the women who “began disappearing from our city, walking into the night and never returning home.” Rather than be abandoned, they chose to do the leaving themselves, and in doing so, transformed into wolves. Wolves are symbolic and laden with meaning. Even the very image of a wolf evokes certain associations like freedom, ferocity, untameability, being a predator as opposed to being easy prey. But of course, the official reason for the missing women was that they were being eaten by wolves, that women have “something in our biology that made us more delicious, entirely edible.”

One night, the narrator discovers a pregnant wolf on the brink of death. She brings the wolf home in hopes of nursing it back to health, but it dies, so she performs a caesarean. Instead of cubs, there was a human infant. This infant was growing unnaturally fast and since there was nothing to feed him, she fed him his own mother. This is probably symbolic of the way mothers give their lives to their children, especially their sons, and the way their sons readily take and take and take until nothing’s left.

“I was his whole world since birth. If he still left me, it would prove once again that there was something deeply and irreparably wrong with me.”

To prevent the wolf-boy from leaving, she forbids him from ever leaving the house and locks him in. This becomes difficult when he becomes a horny teenager. She lets him use her laptop to occupy himself. One day, she realises that he has turned into a man. At the same time, the town has become truly deserted and soon there will be no one left but her. There was an evacuation notice that she missed. They shut off her lights, and soon it will be gas and water. During a full moon, she lets him into her room and they copulate, and the next day she finds her body changing—she grows claws, teeth, fur—while the man is somehow turning more human, as if he transferred his wolfness to her. In the end, he unlocks the door and she runs free, which I read as her finally being unfettered by her past. She is no longer just another woman who continues to wait around for a man who will never return. Love that for her.

(4) ‘K’

In short, this story is about a student dorm room that’s being haunted by the ghost of an ex-student, K, who went missing decades ago and was never found. I love poltergeist stories. Kara is assigned the room that is rumoured to be haunted. She knows for certain it is because the ghost of K shows up at night, crawls into her bed, and speaks to her in her dreams. She becomes obsessed with finding out more about K, thinking that K wants her to find out how she died. She thinks that there is someone to blame for her disappearance, that it wasn’t voluntary.

“I don’t know if it was love either, but it’s true that I couldn’t look away. I savoured our nights beside each other, forgetting that K could never be mine. Something took her.”

She conducts a seance with some mysterious girls who nobody knows about, and during the session, she senses someone step out of her body and circle the room before climbing onto her. The next morning, the maintenance hatch in the ceiling is open. Inside is the camera that went missing with K years ago, some developed film, and an old diary entry revealing that K had a relationship with the antisocial groundskeeper who lives on campus all year. Kara finds out from the groundskeeper that back in 1985, K invited herself into the groundskeeper’s cabin and clung onto her. It is revealed that the groundskeeper is not actually just some older woman, but something otherworldly, a “beast.” And K had voluntarily allowed herself to be consumed by it, wishing to stay forever.

“Using one long fingernail, the creature split a seam from her own chin down to her clitoris and opened herself like a winter coat. K crawled inside that warm, wet womb and remained, unborn in the body she loved so much.”

There’s no easy, straightforward way to read it. I think any interpretation of a story like this will be tainted by each reader’s personal life experiences, their own schema. For me, this story seems to be about that very specific experience of being a younger woman (who is inexperienced and impressionable) and falling in love with an older woman who also functions as some kind of pseudo-maternal figure, simultaneously wanting them and wanting to be like them, and ending becoming subsumed by these twin desires, losing your original sense of self in dependency. Kara started out looking for a culprit, but I think the story is saying that there’s no real villain in this situation. In fact, the groundskeeper warns Kara not to get too involved with K, suggesting that K herself was not ordinary.

“‘You’ve been feeding her all this time, making her bigger and hungrier. Do you even know who she is?’ the groundskeeper asks.”

Was Kara’s obsession with K the result of K deliberately haunting her? Or was K—the thing that had an actual form hanging around her room—partly a manifestation of herself? Kara says, “Sometimes I feel like I am her, she is me.” and she muses on how her name also starts with ‘K.’ In a way, K can be read as her past or her reputation of being a compulsive liar, something that deters other people from believing what she says or befriending her. Honestly, without mincing words, Kara is a friendless loser.

“K has never appeared to me outside our room—not yet. But there’s another shadow: the me who gathered and grew in the corners of my bedroom at night long before I came here, long before I’d heard of K at all. At first I thought I would start fresh without her, leave her at home with my parents and old stuffed toys, but I realise now I can’t. She grows stronger year by year, filled out by every lie I speak, every story that obscures my true story.”

Maybe there really is a ghost haunting the dorm room. Or maybe K only begun taking on a real-ish form after Kara arrived and brought her duplicity and her double selves. Both Kara and K were social outcasts, so perhaps it was a case of like attracting like, but that is the sort of comforting lie that Kara tells others. The ending baffles me—as Kara narrates this new story of a lie, saying that K had never existed, the beast and the ghost eat her up in what can only be described as a gory, twisted ménage à trois. What could it mean? It’s clear that this was the outcome Kara wanted. Was she suicidal or did she keep lying because she wanted some kind of consequence? Or did she just want to be consumed? Interesting story.

(5) ‘In the Winter’

This was one of the most abstract stories of the collection. The narrator is recounting a time when she was a university undergraduate looking to attract someone.

“Was I lonely back then? Of course I was. Who wasn’t lonely ‘back then.’ In the winter I’m pretty because the loneliness makes my face slack, my eyes intense. There are no stories without loneliness.”

She succeeds, and when invited back to his room, she follows. She lies down on his bed unprompted, which is an obviously flirtatious move although there is nothing romantic about this story or the way that the narrator views this incident. She thought they’d have sex, but he just held her down:

“It was a strange way to come—tights pulled only to my knees, treated a bit like a fleshy little vegetable that had to be held down and scraped clean of seeds—but it worked. Sometimes sex isn’t sexy, just effective.”

I thought about why the sexual encounter was compared to such a mechanical act. I’ve removed seeds from vegetables so many times in the course of cooking but now I will always think of it as a sexual-but-not-sexy thing. One conclusion I reached was that this story was actually about hook-ups.

“How many orgasms does it take to achieve intimacy? How many times does a thing fuck you from behind before you realise you only ever saw him in the woods, in the cafeteria with meat between his teeth. In that classroom, where you were both supposed to be the closest to human, with his hair combed smooth, coat buttoned, scarf tight, he looked completely different. . . the hairs on his knuckles look thicker than you remember . . . Was I the creature, or was he?”

Towards the end, there’s a suggestion that this guy is something of an animal, that whoever he was in a normal classroom setting surrounded by other people and therefore required to be at his most human is not who he actually is. She doesn’t know who he is, and he doesn’t seem interested in knowing who she is. They’re both alienated from each other. What stuck out to me was how even during sex, the narrator was dissociating, looking at his hand and comparing it to hers and not really being fully in her body but partially out of it. It’s a lonely way to live.

(6) ‘Anomaly’

This story reminded me a lot of ‘This is How You Lose the Time War’ because the premise is that there was an ongoing time war in the future:

“Highly trained time agents with conflicting political agendas waged a silent war on our streets over issues we hadn’t even conceived of yet. Envoys from the future, who we’d come to know as temporal diplomats, informed us that these were the crucial years, when our timelines made contact for the first time, and the human world surged with new possibilities.”

Because of these temporal diplomats and the uncertainty of what exactly might negatively affect the future, people became afraid to interact with each other because “even conversation was risky.” And of course, given that this is 2024, the solution is… an app. Lol. People used apps to check who the people in the room were and how they were related to themselves. If someone didn’t have any connections, they would be treated as potential threats, perhaps an envoy from the future here to change the course of history. Honestly, time travel would make it so easy for people to commit timeline terrorism.

What tickled me about this story was how the narrator is living in a literal sci-fi world but her main concern is still being on the dating app and matching with somebody. Like, the girl’s just trying to get a date, man. The options are dismal. The people she matched with suck at pick-up lines and she even ended up matching with someone in her company, which is my personal nightmare. She decided to go on a date with someone she matched with because he had tickets to an “anomaly” (more on this later). And all the while, she’s working a shitty customer service job where the bosses are trying to extract every ounce of labour on company time as they legally can by creating a “horrible kind of surveillance state”:

“Our cubicles were replaced by soundproof booths with transparent walls . . . every inch of our workspace was now visible to the managers, who paced the aisles between meetings like wardens. Unable to pull out our phones or swipe onto an online shopping tab when we were ahead on our numbers, support agents made existential eye contact with one another during phone calls.”

Definitely satire. I get it. It’s actually really funny but sad because I remember hearing a friend tell me about how she hated open office plans, as well as hot-desking which I understand to be people not having a designated spot in the office everyday and being expected to be able to settle down with their laptop anywhere and get to work. It seems to be the in thing now in the corporate world. I’m really fortunate in that I still get a fixed desk with some modicum of privacy. If I had to work at a big table with the rest of my colleagues with no walls between us and everyone can see my screen and hear my phone calls, I would quit. I’m so serious.

So the narrator goes on the date because she’s never been to an anomaly, which is a tear in the space-time fabric. It’s a kind of portal between two worlds, not necessarily in the same universe. Sometimes, when both sides are stable and close enough, the government will monetise it:

“Within months of determining that walking through an anomaly was mostly harmless—like going through a tunnel—as long as you went with a buddy, governments established protocols and booking systems and exorbitant fees. Predictably, humanity couldn’t invent anything without fucking up the environment and commodifying what was left . . . The necessity of traversing in pairs made it a coveted date spot, equipped with a mini train that drove from one end to another and stands that sold locally made pies, cider, and fried cheese curds. Tickets needed to be purchased months in advance.”

This was so funny to me because I can just imagine this happening in Singapore and then becoming a listing on Klook or people fighting for tickets on Ticketmaster. I don’t understand why, but it’s true that no matter what it is, people will find a way to make money off of it. It can be a crime scene and someone will be there trying to provide a polaroid service or souvenir postcards.

The last thing that felt very ‘social commentary’ about this story was how the narrator was still very hung up over her ex despite her decision to get back on dating apps, and she goes on a date with this guy because he’s offering her something she wants and not because she is emotionally available or interested in him, and he is also going on a date with her because his ex dumped him and he ended up with tickets that he got for her. They’re just two people yearning for a genuine connection but unable to give it or find it. Something incredible and out of this world can be right in front of her but it’s reduced to just a backdrop to her personal tragedies.

(7) ‘Lemon Boy’

Nothing much to say about this story. It’s about a girl who goes to her rich friend’s house party and she meets a boy with lemon-yellow hair, hence the title, ‘Lemon Boy.’ She doesn’t know his name and he doesn’t know hers. He tells her that his ex is there, but she shouldn’t be because he saw her die. She spends the rest of the party trying to look for him to find out more about this ex of his.

He tells her that his ex was convinced that there were holes opening up all around, all the time. He didn’t see the holes but he said that he did because he liked how she looked. Eventually, his ex realised that he didn’t actually see the holes and that she was the only person who saw them. They had a fight, and when he saw her again, she “no longer looked desperate but completely blank.” That was when he started seeing the holes. He tried to yank her away but he ripped her body in half and realised she was already dead, then her top half got sucked into the crowd too and she just disappeared. After that, he goes to parties that might have holes and he keeps running into her.

Lemon Boy brings her to the basement and points out a hole in the wall. He climbs in, saying that his ex is waiting for him. The narrator says that she’ll wait for him to come back, but she doesn’t stick to it and leaves. By the way, the whole time she’s hoping to hook up with him, but he’s obviously hung up over his ex so she leaves him be. The narrator recounts that afterwards, she kept fearing that holes were going to pop up around her. I don’t know what this story means but if you have a theory, please let me know.

(8) ‘Supergiant’

This story could be a Black Mirror episode. The narrator is an idol who just performed for the very last time before her company retires her. Turns out, she is some kind of android wearing a skin, and retirement means death. She chose this life for herself, desperate to leave her small town and become somebody. Her manager chose her because she was “the least interesting person who auditioned,” and that she “had absolutely nothing to give but wanted everything.” This boundless desire and ambition—this hunger—is what characterises the narrator. She let her consciousness be transferred to another body made of metal and electricity because she wanted always “to be at the centre of things,” the centre of attention.

“ . . . the procedure would make me so perfect I’d be untouchable. One of those celebrities with flawless skin and bright eyes who were never seen in person. A face so beautiful you could lose your mind . . . There’s barely anything left of the person who grew in her womb, just a bit of organ tissue, a few nerve endings.”

Aside from her time on stage, the narrator doesn’t have a life. Her livestreams are pre-recorded, she can’t go to afterparties or have a life, and she doesn’t have any loved ones. She exists purely to be an idol.

“The world is crisp onstage, every light a sharp thing that almost pricks me. Once it’s over, my whole sense of self wobbles. I don’t know who I am offstage. This body doesn’t feel like it’s mine when it’s unchoreographed.”

This story also reminded me a lot of ‘Eight Bites’ by Carmen Maria Machado because of how the narrator’s desire for fame and beauty led to this bisecting of the self, each half taking on life of its own. We find out that her one and only companion named Less, her makeup artist who’s also her caretaker and the only person allowed to touch her, is actually the remainder of what the company took.

“I always wondered what had happened to my face, my bones, my body. I thought they must’ve been thrown out, not repurposed into whatever Less is.”

When Less takes care of the narrator and treats her tenderly, it is, in a way, a form of self-care. And for the narrator, she finds that she does love Less and no one else, which Less finds “so fucking sad” because Less didn’t love herself, who she considers as discards. Less loves the narrator for being her alt-self who went on to live the life she always wanted through which she can live vicariously. In the end, when the narrator wishes they could reassemble and become one again, it’s self-acceptance.

(9) ‘Nip’

This is another rather abstract story. The narrator is some kind of supernatural entity, almost like a ghost, somewhat like a genie in a bottle. They’re attached to Lucy, a journalist, and once a year, Lucy drives them to a hotel where the narrator will then “become blood and bone for her as a treat.” The narrator’s corporeal form leaves residue everywhere all over the room. They’re lesbians, if you can consider their relationship that way.

I really don’t know what the narrator could be. At first I thought they were a travel-sized bottle of body soap or essential oil or liquid weed because it lived on a shelf and a plastic bag, and in Lucy’s bra. They can be scattered throughout a hotel room. They then lived in Lucy’s purse and Lucy would put them on her dashboard to talk to. Lucy also poured them into her bath water, and while bathing, she picked up the bottle and declared her love for it. From the time they first took on a corporeal form, they’ve been together for six years. Lucy does have other lovers but the narrator doesn’t mind.

One day, during one of their trips, they bump into someone Lucy used to know, a man named Nolan. Lucy obviously wants to spend more time with Nolan and allow his presence to hijack their annual getaway. The narrator starts to realise that real bodies are actually “wobbly and changeable” and thinks to herself that they “can do it too.” They start to shape-shift into what Nolan looks like, which understandably freaks him out. The shape is too difficult to hold so they start to disintegrate, and Lucy catches what she can in her palms and drinks them down.

This is one story I really cannot settle on a satisfying interpretation. I don’t even know how to describe their relationship. The narrator calls Lucy their “sometimes-lover” and says that they are in love. It’s long-term but not committed or exclusive, even though it is committed and exclusive for the narrator. It’s a stretch, but maybe this is about being kept on the back-burner or treated like a convenient back-up? I don’t know. Maybe you’ll know.

(10) ‘Natalya’

This story takes the form of an autopsy report, so each subsection has a title like “Gross Description,” “Evidence of Injury,” External Examination,” etc. The narrator is a doctor performing an autopsy on the body of an older woman he used to love back when he was a teenager. The narrator used to be suicidal and tried to drown himself once. He also cut himself a lot. They met when his family was in Maine. The woman was married to an older man from her hometown in Moscow but was having affairs while living in America. The narrator eventually left Maine but never properly said goodbye to her.

Eventually, the narrator meets his wife in university. He studies to become a doctor. He goes to therapy but still thinks about their kitchen knives. He also thinks about his ex-lover throughout their years apart even though he doesn’t take action or try to find her again. Her corpse shows up at his job one day, and he finds out that she has taken her own life. It is suggested that he wonders if he was the one who passed the bug to her, since being suicidal can be contagious. I don’t have an interpretation for this story.

(11) ‘Persimmons’

Placing this story at the end had the effect of closing the collection with a punch. In short, it’s about generational trauma and the burden of being the eldest daughter. In long, well, I don’t quite know how to describe it beyond the usual standard terms like ‘speculative,’ ‘futuristic,’ ‘dystopian,’ et cetera. Listen to the wacky premise:

Uma is an eighteen-year-old girl living on a faraway planet that’s tied to her bloodline. When her ancestors first arrived on this barren colony, there was one persimmon tree. That tree chose one woman and promised her arable land, impregnated her, and laid down two rules. (1) None of her descendants can eat any fruit. (2) When asked, one of her children must be sacrificed to the tree. Everyone on the planet knows about this prophecy (or more accurately, curse). Uma was unlucky enough to be chosen even before she was born and before she can pass down the curse to a daughter of her own. She wakes up one morning and finds that it will be her last day of existence.

“‘Can’t you act like you want to be my mother, just for today?’ Uma asked softly. She wanted to feel like something that could be loved, if only for one night.

‘No,’ her mother replied, never one to sugarcoat. ‘I’m sorry. I can’t.’”

The central relationship in this story is between Uma and her mother. Her mother is described as a “cold” and “spiteful” woman who never showed her affection and who seemed to “liv[e] in such shame, avoiding any mention of their birthright.” Her mother never shared with Uma stories of her own childhood or her own fears growing up in the shadow of this curse. When Uma talks of leaving the planet, her mother cuts her down and tells her that it’s futile. It is only right before Uma gets taken that she breaks down and tells Uma the reason she didn’t allow herself to love her daughter.

“I wanted to be your mother, I really did . . . But how could I? You were never mine. You came out of me the colour of a ripe persimmon . . . You hardly saw me, and you reached at the window for that tree like it could hold you. Even now. Look at me. Me. I’m your mother.”

It is at this point that I think Uma fully realises that her mother is not to blame. Her mother was not her jailer; her mother was also a girl carrying the same burden, and it was either pass it down or continue to live in fear. The only way to get some semblance of freedom from the burden of her lineage is to transfer it, to inflict generational trauma onto another, to bring someone new into the world just to prepare them for sacrifice, which is exactly what Uma’s mother did. Uma would have readily done the same if she could conceive in time, so she’s in no position to judge her own mother.

I think what motivated Uma to go f*ck it and eat fruit and kill the whole planet was jealousy. If Uma’s mother does have another daughter after Uma’s death, she will be treated differently from the firstborn; she will be “rocked and held” and her mother would “mak[e] flower crowns and smil[e]” because her mother would know that she gets to keep this one, she gets to love this one in a less complicated way. As the eldest daughter, Uma was never and never will be afforded such privileges.

But what’s all this for? Uma was denied a normal childhood, shunned in school, and is about to get ripped apart to die a gory and gruesome death, and for what? For the rest of the town to continue living comfortably on this planet for another hundred years. One death in exchange for continuity doesn’t sound like a bad deal, but that’s if you’re not the one dying. She’s expected to obediently go to her own execution, to give up the last thing she has to give up so that others can benefit. The townspeople, who can be said to represent the other beneficiaries of the eldest daughter’s sacrifice, don’t care about her or her maternal predecessors beyond their function.

“It was clear to her now that the town never saw her or her mother as anything close to human . . . She would be a martyr. The townspeople would paint her for centuries, write poems about her newborn-baby smell, how beautifully she had come apart.”

By eating of the forbidden fruit, Uma chooses to take everybody down with her. She’s not going to prioritise others over herself the way she’s expected to. She doesn’t allow the townspeople to benefit from her death for generations to come. She is also sparing her potential future sister’s daughters from having to carry this heavy burden. I mean this in a complimentary way: she is being selfish. It is an act of revenge, a rejection of the destiny foisted upon her from birth.

“The townspeople continued to eat even when all the fruit was gone. They bit down on any soft flesh they found, tearing, crunching. The crowd swallowed her mother. Her mother swallowed the crowd. The courtyard became one large mouth, and Uma twirled at its centre, arms outstretched.”

The death of the entire town (and by extension, the entire planet), is the alternative to Uma’s willing sacrifice. Without Uma, they lose their senses end up cannibalising themselves, leading to the end of this human colony. When I read this, I recalled what the father of that murdered Olympian, Rebecca Cheptegei, said to the press about how his daughter “has been helping out in many ways” because they have young children still in secondary school. “I don’t know how we are going to cope with this challenge to ensure they complete their studies.” he said. What this means is that they were relying on their daughter to fund their lives, especially the lives of the younger children they chose to have after her; their daughter was the family’s breadwinner. Now that she’s gone, they’ve lost a significant source of income, so they’re distraught. It’s very telling.

“Her mother stared up from the front of the crowd, smiling. She saw the unnatural fruit flesh and knew.”

Uma’s mother is different. Upon realising what her daughter had done, Uma’s mother smiles, which I read as acceptance or even pride at Uma’s choices. She knew that her daughter wasn’t going to be led to slaughter, that her daughter was making one last choice for herself, albeit the only choice she could ever make. Everyone was going to pay for the way they exploited Uma and her family. And she’s glad for it. F*ck them all, indeed.