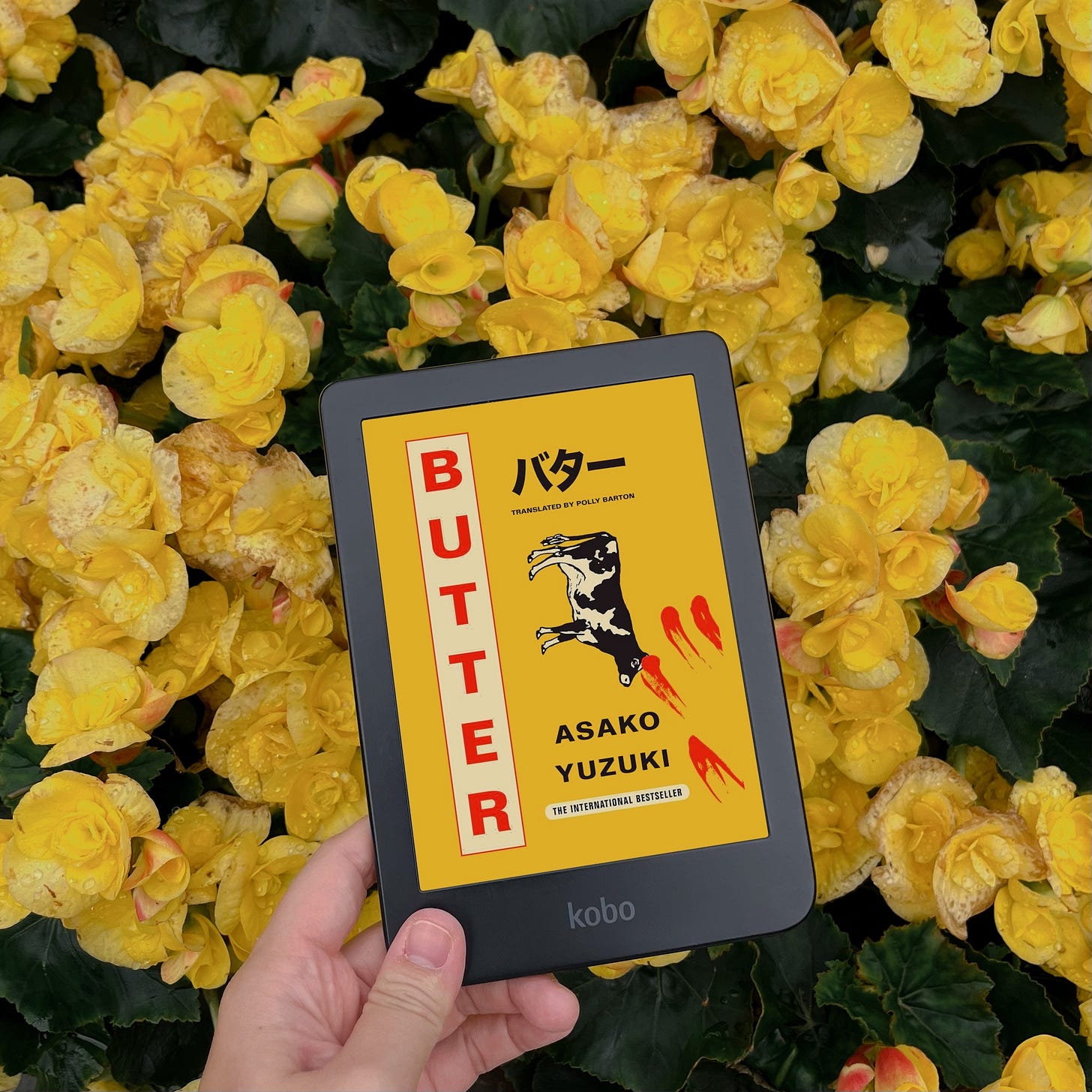

I received an email via NetGalley promoting the ARC of Butter by Asako Yuzuki, which is officially publishing later this month on 29 February 2024. It was available on demand, which struck me as strange because I was under the impression that translated Japanese works were really popular and needed to be wishlisted. I knew nothing of this book but decided to give it a shot purely for the title and translator, whose other works I’ve read before. Before diving into my review, I’m going to fully summarise the book and include spoilers.

The main character is Rika, a journalist for a big media company. She’s a workaholic who hardly eats and barely meets her boyfriend (who is literally a long-term long-distance low-commitment casual boyfriend lmao). Rika is hoping to get an exclusive scoop with a notorious alleged serial killer, Kajii, who has been imprisoned and is awaiting trial. It was a huge case that was covered by every newspaper, magazine, and tabloid. Sordid details of Kajii’s past were made known, such as her having dated a man in his forties while she was just a teenager, what she cooked for her three victims before they died supposedly of natural causes, and the classmates she met at a prestigious cooking school. Kajii is known to hate journalists and other women. The novel begins with Rika visiting her only friend since her schooling days, Reiko.

Reiko has aspirations of having children but has been unsuccessful in the past couple of years. She quit her job to focus on conceiving and even started visiting fertility clinic. She prepares a wonderful meal for Rika and gives her a suggestion on how to get Kajii to agree to meet, which is to ask her for a recipe. Rika took Reiko’s suggestion and it actually worked, so Rika went down to the detention centre to meet Kajii. Kajii does not want to talk about anyone or anything besides food, so she tells Rika not to bother contacting her until she has tried eating rice with butter and soy sauce. Each time, Kajii gives Rika instructions on what to cook/ eat and Rika returns with an account of how she felt. This becomes the start of their ‘friendship,’ if you can even call it that. Rika is eager to get into Kajii’s good graces so she can ask for an interview, but as she is drawn into Kajii’s world of food, she finds herself changing as well, physically and mentally. She starts to develop deeper relationships with others in her life, such her colleagues and a work acquaintance she wasn’t very close with. Rika answers Kajii’s questions about her personal life and past to gain her trust and succeeds in getting Kajii to agree to be interviewed. Rika also begins to side with Kajii, thinking that if those men neglected their health to the point of fatality just because of a woman, it is not her fault.

The turning point occurs when Rika is instructed by Kajii to visit her hometown in Niigata. Reiko tags along, ostensibly to help take photographs and keep Rika company. They meet Kajii’s mother and sister in Kajii’s childhood home (which is flea-ridden....yikes) and visit a dairy farm nearby that’s run by an old acquaintance. Rika meets the acquaintance alone and finds out that Kajii wasn’t the talk of the town as she said to the press. She was actually just a random nobody who had a reputation for eating a lot. Nobody particularly paid attention to her or sought her out. On top of that, she got her period at the age of nine and her body was developing rapidly way ahead of her peers, exacerbating her friendlessness. Reiko reveals that she’s been doing some investigating of her own. She found out that there was a pedophile who was harassing the schoolchildren, and that the period he was active corresponded with the time that teenaged Kajii supposedly started a relationship with a middle-aged man. Reiko confronts Kajii’s younger sister, who admitted that the pedophile actually went for her in the barn and she injured him with an axe before getting away. She ran to Kajii seeking help, and Kajii patched him up and made bentos for him. That was the extent of their relationship, but Kajii wanted people to think that she had a romantic liaison because it fed her ego.

The pair return to Tokyo, but Reiko disappears and becomes completely uncontactable. Her husband asks Rika for help and admits that he has been feeling pressured by Reiko’s desire for children and has been distancing himself from her as a result. Rika has a hunch about where Reiko has gone after finding a magazine article in Reiko’s house. At this point, the POV switches over to Reiko’s. She has managed to hunt down one of Kajii’s past boyfriends, and it was actually at his apartment that the police arrested her at. Reiko also visited Kajii in prison as she felt that she was losing Rika to Kajii. She created a fake dating profile and pretended to be a battered wife seeking refuge. The man’s a total slob with a shit personality to boot, but Reiko wanted to find out if he was the pedophile from Kajii’s hometown all those years ago. Reiko also tries to cook and clean for the man, but he was unappreciative and rude no matter how hard she works. This puts Reiko in a spiral, because she had been unconsciously competing with Kajii and she could not understand why the man would fall for Kajii’s cooking and attention but not her.

Rika shows up and takes Reiko away. She shelters her friend in a friend’s uninhabited apartment. Rika’s new friends all chip in to help watch over Reiko, sleeping over most nights, and they start becoming real friends living in a temporary commune-like environment. Reiko spends her days sleeping and only eating a little but gradually recovers enough to restart communication with her husband and work towards reconciliation. They start attending lessons at the cooking school where Kajii learnt how to cook fancy dishes for her boyfriends. There, they meet the women who had interacted with Kajii and find out that she threw a fit and trashed the kitchen when they wanted to cook a turkey. Kajii stormed out then, and was arrested two months later. Rika publishes her six-part story about Kajii, to great success and readership.

However, a rival magazine publishes a story by Kajii’s new husband, whom she secretly married while still in prison. The article paints Rika as an obsessive fan who imitated Kajii because she had a crush on her, and even went so far as to reveal the personal things Rika shared about her father and boyfriend. Kajii’s husband also says that they are going to publish an official memoir to set the story straight, as everything Rika wrote was lies. This is a huge blow to Rika, who feels that Kajii was ruining her life as revenge for having abandoned her and pointing out her friendlessness. The public is also lambasting Rika and her appearance, so she has to take a break. She doesn’t want to let Kajii win so she continues to live. She realises now it is not so easy to exonerate Kajii because her actions have had severe consequences on others. Kajii will likely face life imprisonment because of all the deaths she indirectly caused.

In her apartment alone, Rika mopes and spirals and barely eats until Reiko invites her out for a talk on the Islamic practice of fasting. Reiko tells her that she has many supporters who don’t believe what Kajii’s new husband is saying. Rika put two and two together and remembered Kajii’s old blogpost about cooking a turkey shortly before she was arrested. She suspects that Kajii planned to invite her cooking school classmates over for turkey and make amends, as all this time, Kajii actually craved friendship with other women. The reason she dated older men and acted like she was better than everyone else was because she was deeply envious of other women and deeply lonely. Reiko manages to confirm Rika’s suspicions, which inspires Rika to cook a turkey for all the people in her life.

Rika puts down a mortgage for a new apartment with many spare rooms so that she will have a reason to continue employment, as well as to provide a refuge and safe space for anyone in her life who needs it. She spends five days bringing her vision of a turkey party to life. The party is a great success and she comes up with a plan to make a Japanese-style breakfast using the leftover turkey. At her job, she will be moving to a different department and doing a series of interview with the women whose lives were negatively impacted by Kajii’s actions, including herself. Content with her life and relationships, she goes to sleep.

End of synopsis.

Women’s unhealthy relationship with food is a huge theme in this novel. It’s no secret that many Japanese women are pressured to remain thin and glorify disordered eating. I don’t know how many times I’ve come across Twitter or Instagram accounts run by stick-thin women whose very popularity lie in their weight loss journey and homemade exercise videos. Once they make it big, they invariably start shilling some konjac packet drink that is meant to help you feel full so you can manage your hunger pangs as you diet.

It’s not a recent thing. Growing up watching movies like Bridget Jones’s Diary and shows like America’s Next Top Model, preteen me internalised the message that if you’re fat, nothing else about you matters. Fat is good only if it’s in the correct places. I witnessed with my own eyes how fatter girls were instantly written off as romantic options and treated like furniture. The women’s magazines that my mother occasionally bought constantly featured ‘magical’ work-outs to help you lose weight or lose fat in a specific area (which is not how it works!) or so-called fat-burning lotions, serums, and oils (also not possible). Simply by existing, I was inundated by a barrage of messages telling me that being fat is akin to sin; if you ever want to be loved by a man, you better not be fat.

Every woman character in Butter experiences this. At the start, Rika “took care that her weight never exceeded 50 kilos . . . Her slim physique ensured that, despite not being a remarkable beauty, she would still be complimented”. She knows that being conventionally thin helps people take her seriously, which helps her job. However, after gaining some weight, her boyfriend and best friend criticised her for it. As for Kajii, she was treated very harshly by the media companies and public after being thrust into the spotlight, and the morbid fascination surrounding her case was in large part due to the fact that she was unconventionally unattractive. Even the men who were wrapped around her little finger had no qualms about mocking her physique behind her back and using very derogatory language.

The thorough line of action in this novel is how Rika’s beliefs undergo an extensive overhaul before she finally arrives at self-acceptance and peace. I would go so far as to argue that Rika needed to meet Kajii for her transformation to have been possible. Kajii is a direct foil to Rika’s boyfriend—while Kajii encourages Rika to eat whatever makes her body wants, her boyfriend purposely brings her to low-calorie restaurants so she can slim down. Her conversations with Kajii taught her to reject society standards and made her realise that “[s]he was tired of living her life thinking constantly about how she appeared to others, checking her answers against everyone else’s.” Once she disconnected herself from her boyfriend’s disapproval, she was able to move forward, and it’s all because she met Kajii. Their relationship may have been warped and toxic, but it was this connection that triggered Rika’s eventual liberation from internalised patriarchal standards and misogyny.

The novel also comments on failed relationships between men and women. There is a clear pattern of women reaching their limit and choosing to leave. (Maybe this is a radical aspect that got this novel labelled “feminist”?) Rika breaks up with her boyfriend because she found out how misogynistic he actually was, Kajii’s boyfriends constantly denigrated her in front of others, Rika’s parents divorced after her father got verbally abusive, and Shinoi’s wife left him because he was a neglectful father. Rika muses that “[a]t the end of the day, men were not looking for a real-life woman, but a professional entertainer” who would dedicate themselves to soothing and comforting them. The useless grown men in the novel point to a criticism of the way men in real life expect to be mothered but also subservience, as well as how women in real life get married because it’s expected of them but end up very unhappy. Divorce actually restores the women to a happy state of self-sufficiency, while their ex-husbands rotted and wasted away.

For Rika’s mother, not only was she groomed by her university professor, she had to endure living with a man who could not be pleased and whose presence did more harm than good. Rika recalls there being a “tense atmosphere that had prevailed when her father had been around.” I can really relate to this. It’s genuinely so soul-sucking to live with someone who could explode at any given moment so you’re forced to walk on eggshells around them. I don’t understand why people think that divorce definitely harms the children regardless of context. Isn’t witnessing the violence (yes I think it is violence) first-hand and frequently actually more harmful than removing the parent causing the problems? It’s also not true that a child needs both parents around, especially if one parent is abusive. Rika continues to have a good relationship with her mother in part because of the divorce enabling them both to live peaceful and uneventful lives. Reiko, who is estranged from her parents, also comments that Rika’s mother “did a far, far better job as a single mother than [her] parents managed as a pair.”

Notably, Reiko’s failing marriage also brings up a point about how much women are socialised to want the things society tells them to want, such as marriage and children, both of which are contingent on heteronormativity. Reiko asks, “Why do we think that nothing will ever happen unless a man singles us out? Why do we have to wait to be chosen, doing nothing, as if we were dead or something?” For many women, they grow up believing that all the defining moments in their life can be brought about only with a man, but if you chase after one you instantly become undesirable and further from your goals. On paper, Reiko is the perfect homemaker. She’s beautiful, well-dressed, very good at keeping a house spick and span, and has the stamina and creativity to labour at the kitchen and cook amazing meals. She exists to manifest her perfect home, yet she remains childless with marriage problems.

“What does it mean though, for things to work out between a man and a woman? What state is that indicating? Sometimes you can go as far as getting married and it still doesn’t work out, like in my case. And being desired by men doesn’t always make you happy, as we know from Kajii.” Reiko’s initial fascination with Kajii lies in how confident Kajii seemed. Even while imprisoned, Kajii continues to believe that she would be able to have children someday. In a way, both Reiko and Kajii are unhappy because they’ve been socialised to believe that their primary goal is to become mothers, when society itself is so hostile and unsupportive and men so unsuited for marriage, let alone parenthood.

The preferable alternative, which both Rika and Reiko arrive at, is to engage in self-care. Not the capitalist kind where you buy things and participate in beauty culture under the guise of taking care of yourself. Self-care as defined by this novel is to listen carefully to what your body and heart wants, meeting your own needs, and not be beholden to standards or schedules dictated by other people. If you want company, seek out your friends. If you want your friends to show up for you, show up for them first. If you’re hungry, eat. If you want to eat something, make it for yourself and eat it the way you like. You deserve delicious homecooked meals too; your cooking doesn’t have to be to make a man happy.

“And yet Rika had realised a while back that, even if she were to lose a few kilos, she still wouldn’t pass. However beautiful she became, however well she did at work, even if she got married and had children, society didn’t let women off that easily. The standards were getting higher, and assessments harder. The only way to be free of it . . . was to learn to accept yourself.”

I also liked the revelations that Rika reaches about the necessity of community and friendship. Both Rika and Reiko realise that their romantic relationships don’t fulfil them as much as their friendship. I do think there is a hint of something sapphic between them, especially with Reiko seeing Rika as her Prince Charming (Rika did save her from herself, after all), but it’s not homoerotic. The author is not interested in physical connections or desires like lust. Even physical hunger/ the act of eating is treated as something more than just meeting base needs.

Kajii remains deluded and unhappy because she believes herself enlightened simply because she rejects the societal standards that other women hold themselves to. She is in constant competition with other women in her head. But that is revealed as a mere cope for how she cannot fit in or find belonging. Ironically, she uses her sense of superiority to protect her from rejection but it is what gets her rejected in the first place. Kajii craves refuge and community with other women but is trapped in her archaic beliefs of a woman’s value lying in how well she pleases men. Other women sense that and reject her because her internalised patriachal beliefs intrude upon their women-only safe spaces. Kajii is unable to conceive of a world where women are not selfish by doing things for themselves, such as cooking food with unconventional tastes. Her actions up till the point of her arrest have been a cry for acceptance and acknowledgement, not from men, but from women.

In sum, butter (the condiment) in this novel functions as a metaphor for how if you want to have a good life as a woman (i.e., one that is fulfilling, nourishing, healing), you cannot scrimp on putting in the effort to care for and be generous towards others, especially other women. This idea was first professed by Kajii, but she ironically fails to understand what it means to nurture a mutually supportive friendship. It’s funny how Kajii goes on and on about how she doesn’t want to eat fake things like margarine, only the real good stuff like butter, but she cannot see that substituting female friendships with temporary romantic liaisons with rich old men is settling for what is fake.

To conclude, this quote felt applicable to me:

“[Y]ou don’t have to get through everything alone. You don’t have to always be growing as a person either. The far more important thing is just to get through the day.”

What a mood! Capitalism is antithetical to feminism, I do believe that. This whole narrative of endless progress, endless growth, endless profit, having to set higher and higher goals each year, aiming to exceed expectations and never being content with just meeting them, achieving greater heights, beating the competition, doing better, climbing the ladder, striving to be at the top of the food pyramid, vertical hierarchies, etc—I hate it and I reject it all. We don’t have to be a rat in the rat race. We don’t have to see every situation as a zero-sum game. We can take turns to shine. More importantly, we don’t have to leave anyone behind or measure a person’s worth by what they can produce. There’s a saying that nothing in nature blooms all year round. There’s also a saying that comparison is the thief of joy, but I think the real thief is the pressure we put on ourselves to achieve goals that we didn’t even set, and it all boils down to a lack of self-awareness of what truly makes us happy.

I loved this review and synopsis! I feel like I gained more from the book, thanks!

I love this review so much and your opinions on the book. Defo trying to read it when it's out/when I'm able to 🧈